IT’S BUMBLEBEE BONANZA TIME

Bumblebee Conservation

By: Engrid Winslow

Bumblebees pollinate many of our food crops and garden flowers which means the conservation of the species is vital to our ecology. Some species of Bumblebees are true American natives and are most commonly found in northern climates and higher elevations. Nearly all of the estimated 250 species live in the Northern Hemisphere although there are a few species that pollinate flowers in tropical rainforests in warmer climates. They are social insects that form colonies of around 50 bees with one Queen although only the Queen survives the winter. They commonly build their nest in the ground or in crevices of rocks and are quite good at hiding their entrance.

They are capable of flying (and pollinating) at cooler temperatures and lower light conditions than other bees which makes them important pollinators for plants growing in higher elevations and colder climates that are beyond the reach of other bees. Their plump, fuzzy bodies are a welcome sight that spring is on its way at last. It’s usually the super-sized Queen out and about in early spring as she starts to build a nest and raise brood.

Bumblebees are peaceful insects and will only sting when they feel cornered or when their hive is disturbed. When a bumblebee stings, it injects a venom but unlike a honeybee sting, the bumblebee sting has no barbs. This means that a bumblebee can pull back its sting without the sting detaching from its abdomen and can sting several times. Only female bumblebees (queens and workers) have a sting; male bumblebees (drones) do not. Justin O. Schmidt, author of The Sting of the Wild and the creator of The Schmidt Pain Index rates a bumblebee’s sting at a 2 on the index which starts at 0 and ends at 4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schmidt_sting_pain_index.com.

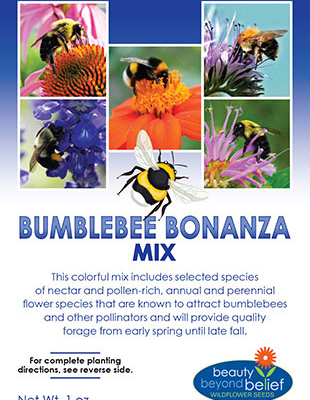

Here at BBB, we specialize in pollinator mixes and our newest one is designed with bumblebee conservation in mind. It is our mission to help you provide nectar and pollen because “the more flowers a garden can offer throughout the year, the greater the number of bees and other pollinating insects it will attract and support.”

Bumblebee Bonanza includes Siberian Wallflower, Rocket Larkspur, Balsam, Yellow Lupine, Arroyo Lupine, Purple Coneflower, Dahlia-flowered Zinnia Mix, Dwarf Mixed Cosmos, Gayfeather, Rocky Mountain Penstemon, Blue Sage, Northern Lights Snapdragon, Purple Prairie Clover, Lacy Phacelia and Beebalm.

Bumblebees are unique because their long tongues can reach the nectar in flowers that other bees avoid, such as penstemons, lupines, larkspur and snapdragons. They collect large amounts of pollen because they have so many hairs covering their little bodies and thrive on daisy-type flowers such as Zinnias, wallflower, cosmos and coneflower. There is a wealth of information available about bumblebees and what you can do to help them. Some of our favorites are info@thebeeswaggle.com and https://xerces.org/bumblebees/.

Remember that the use of synthetic insecticides, particularly the ones that contain neonicotinoids are harmful to all bees. Please avoid using them in your garden, lawns and talk to your neighbors and friends about the perils of using these chemicals. Neonicotinoids are sold under many different names such as:

- Acetamiprid

- Clothianidin

- Dinotefuran

- Imidacloprid

- Nitenpyram

- Thiacloprid

- Thiamethoxam

Let’s all do our part for bumblebee conservation!